For 155 years, African Americans have celebrated independence on Juneteenth

GALVESTON, Texas - When most Americans think of July 4, they think of independence, freedom, liberty — America and all of its grandeur.

But when you ask Nia Miranda what that date means to her, she has a different answer.

"I think of an excuse to have a BBQ, but definitely not independence," Miranda said.

A self-described "ARTivist," actress and filmmaker, Miranda founded Bringing Love Back, which promotes love and unity in the community.

She garnered recent notoriety for confronting two non-black women who were spray-painting "BLM" on a Starbucks during a peaceful Los Angeles protest in the wake of the death of George Floyd.

Miranda is not alone in her feelings about July 4.

While your social media feeds are guaranteed to be full of images of Old Glory, a bald eagle and the Statue of Liberty, don’t be surprised to see less enthusiasm from your black friends.

It’s certainly not due to a hatred of country. After all, Dr. Merline Pitre — a history professor at Texas Southern University — said, "African Americans feel for themselves, this is their country."

African Americans have represented the United States on battlefields, waved the Stars and Stripes at Olympic games and climbed all the way to the Oval Office.

Even before the colonies united, Crispus Attucks lost his life in the Boston Massacre, becoming the first person killed in the American fight for independence.

"They’ve fought, died, blood sweat and tears, but they still don’t have the rights that the White Americans do," Pitre said.

No, "hatred" is not the right word — but neither is "independence."

When the founding fathers declared open rebellion against King George III, proclaiming themselves to the world as an "independent" country, most black people were the furthest thing from free.

It’s not entirely reasonable to expect their descendants to cling to July 4. But that’s not to say African Americans don’t celebrate independence — it’s just celebrated 15 days before Independence Day.

What is Juneteenth?

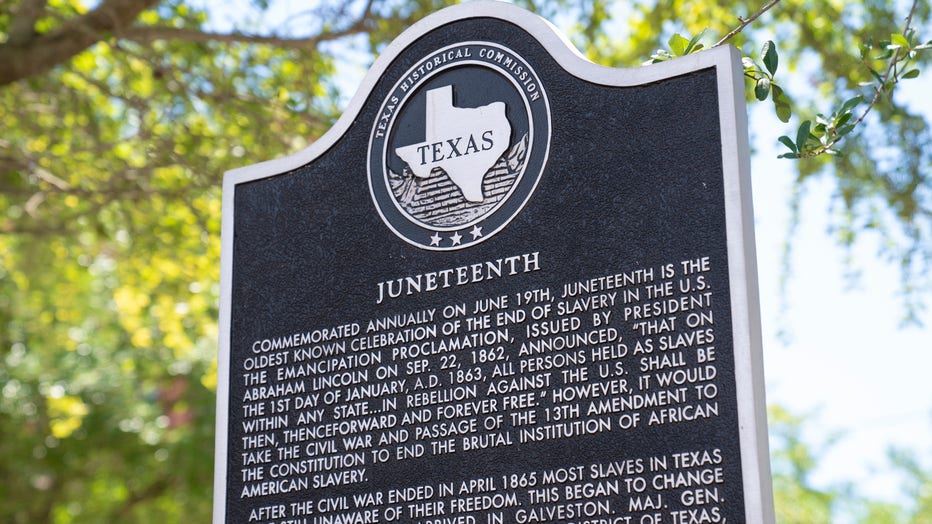

Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration of the end of slavery in the United States.

On the morning of June 19, 1865, the enslaved population of Galveston, Texas woke up in bondage for the last time.

After years of seeing Confederate flags waving in the wind, a ship had sailed into the island’s harbor flying the Star-Spangled Banner.

Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger disembarked the vessel along with more than 2,000 Union troops.

Locals gathered at Ashton Villa, a mansion that had served as a Confederate headquarters. Granger stood atop the balcony and recited General Order No. 3.

"The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free," the order read.

The order detailed a new relationship between former slaves and owners in which black people would work for wages.

But according to Juneteenth.com, many of the freed slaves left celebrating before those words could escape Granger’s lips.

Up until that moment, freedom was only a distant prayer and a dream. But legally, they had been free for more than two years.

Why did liberation take so long?

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863.

It was a wartime executive order that indeed freed the slaves. But Dr. Cary Wintz, a history professor at Texas Southern University, said Lincoln was strategic in the way he crafted it.

Wintz said Lincoln didn’t go after the slaves held in neutral states, as to prevent them from joining the Confederacy. And he didn’t touch the slaves that were already in Union-held states.

As the war dragged on, Lincoln moved toward the passage of a constitutional amendment that would settle the issue of slavery for all time.

RELATED: NFL will observe Juneteenth as league holiday, closing all offices

"The Emancipation Proclamation started the process," Wintz said. "It meant that if the north won the war, slavery would end."

The amendment cleared Congress in January 1865. Though it wouldn’t be ratified until that December, Gen. Robert E. Lee formally surrendered Confederate forces on April 9.

Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. (Source: Galveston Convention & Visitors Bureau)

And even then, it took months for the Confederate troops in other states to follow suit.

News didn’t travel as fast back then as it does today. But Wintz said slaves had ways of keeping up with the status of the war.

Texas never forbade slaves from learning to read, so Wintz said they would get war updates from newspapers. Slaves could also hear the news, as the paper was often read aloud.

Wintz said slaves who ran away knew if they could just make it to Union lines, they would be free. But that wasn’t possible in Texas.

Union forces never invaded, so there was nobody in Texas to enforce Lincoln’s executive order until Granger sailed into Galveston.

Early Juneteenth celebrations

Juneteenth celebrations in the 19th century took place mostly in rural areas of Texas.

Some gathered near rivers where they could fish and ride horses, while others met at church to pray and fellowship.

The liberated were eager to adorn themselves in their finest clothing, finally being free from the laws that limited the dress of slaves in parts of the state.

It wasn’t unheard of for White employers to give their black workers the day off so they could celebrate.

As African-American land ownership became possible, the Juneteenth celebrations moved into public spaces, like Houston’s Emancipation Park or Mexia’s Booker T. Washington Park.

One thing all celebrations had in common was barbecue. A proper commemoration was not complete without barbecue and strawberry soda.

Jonathan Talley, of Roxbury, grills chicken, ribs, and sausage at Franklin Park for the Juneteenth celebration on Saturday afternoon, June 21, 2014. (Photo by Zack Wittman for The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Even in modern commemorations, those two staples are still sure to be present, giving participants a chance to take in the same aromas and flavors as those freed in Galveston.

But even as those traditions withstood the test of time, the celebration as a whole struggled to endure at the start of the 20th century.

Decline and resurgence

African Americans were several generations removed from slavery by the 1900s.

Far too young was this lot to have experienced the hardships of their parents and grandparents. Their reality was the Jim Crow South, and Pitre said it played a major role in Juneteenth’s decline.

"Some felt they were celebrating slavery," Pitre explained. "Blacks were fighting Jim Crow so hard, they did not take it as a group celebration."

Even Texas schools at the time would focus less on June 19, 1865, being the date slaves were freed — opting instead for Jan. 1, 1863.

Juneteenth became more of an oral tradition. Its meaning was primarily passed down through households and black churches.

But in the 1940s, Juneteenth found new life in an unexpected place: the courtroom.

RELATED: The Pan-African flag started as response to bigotry — It became an enduring symbol

Up until that point, black voters remained fiercely loyal to the Republican Party since it was the party of Lincoln.

But that began to change, Pitre said, when many black voters wanted to jump to the Democratic side because it was the majority party and it would give their candidates a fighting chance.

But several southern states had laws prohibiting anyone but White people from voting in Democratic primaries.

After many court battles, black voters earned a victory in 1944 with Smith v. Allwright. The Supreme Court ruled White primaries in Texas were unconstitutional.

Other states ended the all-White primary practice soon after, kick-starting a resurgence in racial pride among black people.

As the Civil Rights Movement dominated the next two decades, tales of Juneteenth found their way out of the darkness and back into the public eye.

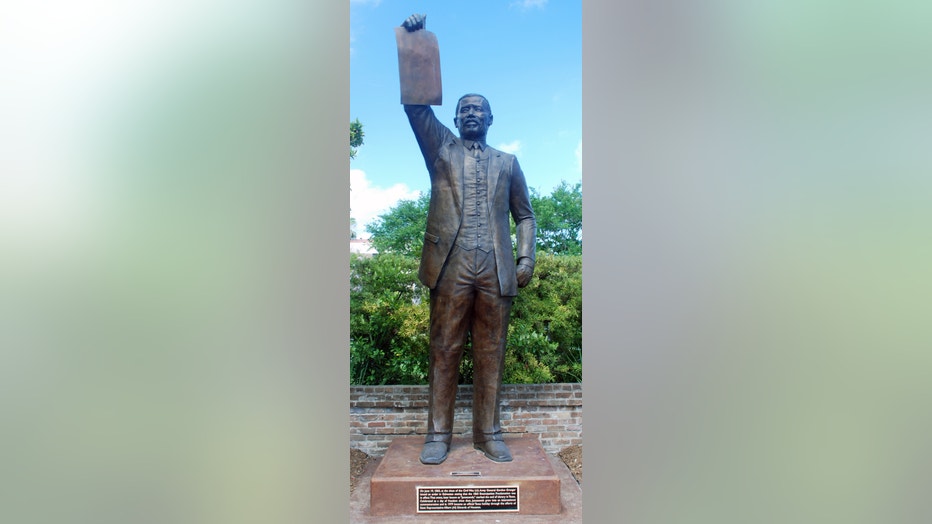

In 1979, Texas state Rep. Al Edwards wrote and sponsored House Bill 1016, which had Juneteenth declared a paid state holiday — making Texas the first state to do so.

The Black Migration of the mid-1900s saw millions of African Americans leave the rural south and make new homes throughout Midwest, North and West coast, Wintz said.

A general view during the 48th Annual Juneteenth Day Festival on June 19, 2019 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (Photo by Dylan Buell/Getty Images for VIBE)

They carried with them the tradition of Juneteenth, which is why celebrations can be found today in places like Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Denver and even Minneapolis.

For years, advocates have asked for Juneteenth to be recognized as a national holiday. While it has not yet succeeded, 46 states and the District of Columbia observe Juneteenth in some capacity.

Still, none of those distant cities commemorate the day quite like Galveston.

Juneteenth in Galveston

Doug Matthews has been a part of Galveston’s Juneteenth celebration for the last 41 years.

His tenure began the same year Rep. Al Edwards had the day declared a state holiday. And for the last 23 years, Matthews has coordinated the city’s celebration.

"Galveston is where it began," Matthews said. "We recognize our place in history and we’re honored. We’re going to always preserve and nurture our history. We’re very proud of our history and the significance of what Juneteenth means to the African-American community,"

Every year, Matthews arranges for a reenactment of Granger’s reading of General Order No. 3.

"All slaves are free," the actor says, pausing for an ovation. "All slaves are free."

Guest speakers of all levels of government have addressed the crowd year after year.

Galveston erected a statue of Rep. Al Edwards, who fought to get Juneteenth recognized as a state holiday in Texas. (Source: Galveston Convention & Visitors Bureau)

Edwards’ children are known to frequent the festivities. He passed away on April 29, 2020, at the age of 83.

The commemoration isn’t limited to just a single day, so visitors can expect 12 to 15 events — including a gala, banquet and multiple parades.

Matthews said the crowd size had been trending upwards since the 2015 event, which marked 150 years since liberation.

But this year, the celebration will look a bit different. They’re encouraging the public not to come.

The COVID-19 pandemic has rendered large gatherings unsafe. Social distancing guidelines make the event nearly impossible to pull off in its usual form.

So instead of the typical pomp and circumstance, Matthews said the city will try to limit the events to just three.

"We’re hoping for a crowd no larger than a hundred people," Matthews said.

Organizers will make hand sanitizer and masks available to anyone attending the reenactment. And instead of having a large breakfast, this year organizers will be donating 700 boxes of food to senior citizens.

Legacy

To a certain extent, Nia Miranda said she had to reprogram herself to accept Juneteenth as a day of freedom for her ancestors.

She pointed out how Juneteenth is not a part of anyone’s curriculum the same way as July 4, or even other cultural observances like St. Patrick’s Day, Oktoberfest or Cinco de Mayo.

In recent years, the day has gotten more attention from media outlets. But for the most part, the tradition is passed on the same way it was a century ago.

African Americans have a complicated relationship with history, much of it erased the moment the slave ships departed Africa. And their ability to trace family lineages often hits roadblocks thanks to the splitting of families at the auction block.

But even though most slaves had already been set free by the time Granger arrived in Galveston, and even though it was only the local slaves who were liberated on June 19, Juneteenth is still a day the entire race can cling to — certainly more so than July 4.

"Juneteenth, one could say, was the beginning of African Americans establishing a usable past," Pitre said.

This story was reported from Atlanta.